Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone) is a β-ketoamphetamine stimulant drug of abuse with close structural and mechanistic similarities to methamphetamine. One of the most powerful actions associated with mephedrone is the ability to stimulate dopamine (DA) release and block its reuptake through its interaction with the dopamine transporter (DAT). Although mephedrone does not cause toxicity to DA nerve endings, its ability to serve as a DAT blocker could provide protection against methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity like other DAT inhibitors. To test this possibility, mice were treated with mephedrone (10, 20 or 40 mg/kg) prior to each injection of a neurotoxic regimen of methamphetamine (4 injections of 2.5 or 5.0 mg/kg at 2 hr intervals). The integrity of DA nerve endings of the striatum was assessed through measures of DA, DAT and tyrosine hydroxylase levels. The moderate to severe DA toxicity associated with the different doses of methamphetamine was not prevented by any dose of mephedrone but was, in fact, significantly enhanced. The hyperthermia caused by combined treatment with mephedrone and methamphetamine was the same as seen after either drug alone. Mephedrone also enhanced the neurotoxic effects of amphetamine and MDMA on DA nerve endings. In contrast, nomifensine protected against methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Because mephedrone increases methamphetamine neurotoxicity, the present results suggest that it interacts with the DAT in a manner unlike that of other typical DAT inhibitors. The relatively innocuous effects of mephedrone alone on DA nerve endings mask a potentially dangerous interaction with drugs that are often co-abused with it, leading to heightened neurotoxicity.

Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone) is a cathinone derivative and structural analog of methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA). Mephedrone is one psychoactive ingredient of “bath salts” along with other compounds such as methylone, butylone and 3, 4- methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). β-ketoamphetamines are being abused at increasing rates due in no small part to the highly restricted availability of precursors needed for the synthesis of methamphetamine and MDMA in clandestine labs and a corresponding reduction in their purity (Winstock et al. 2011b, Brunt et al. 2011). As abuse of β-ketoamphetamines continues to rise, the list of their adverse effects has grown to include cardiovascular complications, agitation, insomnia, psychosis and depression (Schifano et al. 2011, Prosser and Nelson 2012).

As chemical congeners of methamphetamine and MDMA, it is not surprising that the β-ketoamphetamines have many of the same effects as these former drugs on the central nervous system. For example, these drugs block dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) transporters (DAT and SERT, respectively) (Cozzi et al. 1999, Rothman et al. 2003, Fleckenstein et al. 2000, Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012) and they stimulate monoamine release in vitro (Kalix and Glennon 1986, Gygi et al. 1997, Rothman et al. 2003) and in vivo (Gygi et al. 1997, Kehr et al. 2011). Methcathinone causes persistent reductions tryptophan hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) activity and depletion of DA and 5-HT (Gygi et al. 1997, Gygi et al. 1996, Sparago et al. 1996). PET imaging studies in abstinent methcathinone users revealed reduced striatal DAT density suggesting a loss of DA terminals (McCann et al. 1998). The simultaneous stimulation of DA release and inhibition of its uptake mirror the critical elements underlying the neurotoxicity associated with methamphetamine (Kuhn et al. 2008, Yamamoto and Bankson 2005, Cadet et al. 2007, Fleckenstein et al. 2007).

We (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012) and others (Baumann et al. 2012, Hadlock et al. 2011) recently investigated the possibility that mephedrone could cause neurotoxicity like methamphetamine and MDMA. Surprisingly, mephedrone was not toxic to DA nerve endings of the striatum (Hadlock et al. 2011, Baumann et al. 2012, Angoa-Perez et al. 2012). The issue of whether mephedrone damages 5-HT nerve endings remains unsettled as one study documented positive effects (Hadlock et al. 2011) while another was negative (Baumann et al. 2012). In light of the relatively benign effect of mephedrone on DA nerve endings and considering its properties as a DAT blocker, we hypothesized that it could actually protect the DA neuronal system from the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine much as is known to occur with other DAT blockers such as amphonelic acid (Pu et al. 1994, Schmidt and Gibb 1985, Marek et al. 1990) and nomifensine (Poth et al. 2012). We report presently that mephedrone significantly enhances the neurotoxicity of methamphetamine. This effect extends to amphetamine and MDMA, drugs that are often co-abused with mephedrone (Feyissa and Kelly 2008, Schifano et al. 2011). These surprising results cast the abuse of mephedrone in a new light and add urgency to recognition of this subtle and dangerous property of this β-ketoamphetamine.

Materials and methods

Drugs and Reagents

Mephedrone hydrochloride and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) were obtained from the NIDA Research Resources Drug Supply Program. (+) Methamphetamine hydrochloride, nomifensine maleate, d-amphetamine sulfate, pentobarbital, DA, and all buffers and HPLC reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Bicinchoninic acid protein assay kits were obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Polyclonal antibodies against rat TH were produced as previously described (Kuhn and Billingsley 1987). Monoclonal antibodies against rat DAT were generously provided by Dr. Roxanne A. Vaughan (University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND, USA). HRP-conjugated anti-IgG secondary antibodies were provided by Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA, USA).

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) weighing 20–25 g at the time of experimentation were housed 5 per cage in large shoe-box cages in a light (12 h light/dark) and temperature controlled room. Female mice were used because they are known to be very sensitive to neuronal damage by the neurotoxic amphetamines and to maintain consistency with our previous studies of methamphetamine neurotoxicity (Thomas et al. 2010, Thomas et al. 2008, Thomas et al. 2009). Mice had free access to food and water. The Institutional Care and Use Committee of Wayne State University approved the animal care and experimental procedures. All procedures were also in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Pharmacological, physiological and behavioral procedures

Mice were treated with mephedrone using a binge-like regimen comprised of 4 injections of 10, 20 or 40 mg/kg with a 2 h interval between each injection. This binge treatment regimen, when used to inject substituted amphetamines and cathinone derivatives, results in extensive DA nerve ending damage. The doses of mephedrone used presently were previously shown to be non-toxic to DA nerve endings (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012). Mice were treated with methamphetamine (4X 2.5 or 5 mg/kg), amphetamine (4X 5 mg/kg) or MDMA (4X 20 mg/kg) alone or in combination with mephedrone. When treated with two drugs, mice received a mephedrone injection 30 min prior to each of the 4 injections of methamphetamine, amphetamine or MDMA. Controls received injections of physiological saline on the same schedule used for mephedrone alone or in combination with other amphetamines. As a control for the effects of a DAT inhibitor on methamphetamine toxicity, mice were treated with nomifensine (4X 5 mg/kg) 30 min prior to each injection of methamphetamine (4X 5 mg/kg). All injections were given via the i.p. route. Mice were sacrificed 2 days after the last drug treatment when amphetamine-associated neurotoxicity has reached maximum. Body temperature was monitored by telemetry using IPTT-300 implantable temperature transponders from Bio Medic Data Systems, Inc. (Seaford, DE, USA). Temperatures were recorded non-invasively every 20 min starting 60 min before the first METH injection and continuing for 9 h thereafter using the DAS-5001 console system from Bio Medic.

Determination of striatal DA content

Striatal tissue was dissected bilaterally from the brain after treatment and stored at −80°C. Frozen tissues were weighed and sonicated in 10 volumes of 0.16 N perchloric acid at 4°C. Insoluble protein was removed by centrifugation and DA was determined by HPLC with electrochemical detection as previously described for methamphetamine (Thomas et al. 2010, Thomas et al, 2009).

Determination of TH and DAT protein levels by immunoblotting

The effects of drug treatments on striatal TH and DAT levels were determined by immunoblotting as an index of toxicity to striatal DA nerve endings. Mice were sacrificed by decapitation after treatment and striatum was dissected bilaterally. Tissue was stored at −80°C. Frozen tissue was disrupted by sonication in 1% SDS at 95°C and insoluble material was sedimented by centrifugation. Protein was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method and equal amounts of protein (70 μg/lane) were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then electroblotted to nitrocellulose. Blots were blocked in Tris buffered saline containing Tween 20 (0.1% v/v) and 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies against TH (1:1000) or DAT (1:1000) were added to blots and allowed to incubate for 16 h at 4°C. Blots were washed 3X in Tris-buffered saline to remove unreacted antibodies and then incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-IgG secondary antibody (1:4000) for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence and the relative densities of TH- and DAT-reactive bands were determined by imaging with a Kodak Image Station (Carestream Molecular Systems, Rochester, NY, USA) and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH).

Data analysis

Two-way ANOVAs were performed to analyze the dose effects of methamphetamine versus mephedrone on DA, DAT and TH. The effects of drug treatments on striatal DA, TH and DAT content were tested for significance by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. Results of drug treatments on core body temperature over time were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test to determine significance of differences in temperature at individual times after treatment. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 5.02 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com).

Go to:

Results

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity

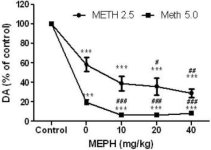

Mephedrone, in doses (10, 20 or 40 mg/kg) known not to cause DA nerve ending toxicity (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012) was administered 30 min before each injection of methamphetamine. Methamphetamine was administered in doses that cause moderate (4X 2.5 mg/kg) or severe (4X 5 mg/kg) damage to DA nerve endings of the striatum (Thomas et al. 2004, Thomas et al. 2010). Results presented in Fig. 1 show that the main effects of methamphetamine dose (F1,40 = 66.60, p < 0.0001) and mephedrone dose (F4,40 = 131.3, p < 0.0001) on DA levels in striatum were highly significant by two-way ANOVA. The main effect of mephedrone given in combination with either 2.5 mg/kg (F4,22 = 35.96, p < 0.001) or 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,17 = 953.9, p < 0.0001) was also highly significant by one-way ANOVA. All treatments with either dose of methamphetamine ± mephedrone caused significantly greater reductions in DA by comparison to the respective control (p < 0.0001 for all). Fig. 1 also shows that mephedrone doses of 20 (p < 0.01) and 40 mg/kg (p < 0.001) significantly enhanced the depleting effects of 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine on DA whereas all doses of mephedrone significantly enhanced the effects of 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine on DA levels (p < 0.0001 for all).

Fig.1

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced reductions in striatal DA. Mice were treated with the indicated doses of mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 2.5 (•) or 5.0 mg/kg (■) methamphetamine (METH) and sacrificed 2d later for determination of striatal levels of DA by HPLC. Data are mean ± SEM for 5–7 mice per group. Some error bars were too small to exceed the size of the symbols and do not appear visible. ***p < 0.001 vs controls and #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.001 or ###p < 0.0001 vs the respective dose of methamphetamine (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Fig. 2a shows that mephedrone significantly increased methamphetamine-induced reductions in DAT levels as determined by immunoblotting. Immunoblots were quantified and in agreement with results for DA, the main effects of methamphetamine dose (F1,92 = 9.48, p < 0.001) and mephedrone dose (F4,92 = 37.56, p < 0.0001) on DAT levels in striatum were highly significant by two-way ANOVA (Fig. 2b). The main effect of mephedrone given in combination with either 2.5 mg/kg (F4,56 = 15.55, p < 0.0001) or 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,39 = 24.84, p < 0.0001) was also highly significant by one-way ANOVA. All treatments with either dose of methamphetamine ± mephedrone caused significantly greater reductions in DAT by comparison to the respective control (p < 0.01 for 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine alone; p < 0.0001 for all other treatments). Fig. 2b also shows that mephedrone doses of 20 mg/kg (p < 0.01) and 40 mg/kg (p < 0.001) significantly enhanced the reductions in DAT caused by 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine whereas only the 40 mg/kg mephedrone dose significantly enhanced (p < 0.01) the effects of 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine on DAT reductions.

Fig.2

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced reductions in striatal DAT. Mice were treated with the indicated doses of mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 2.5 (●) or 5.0 mg/kg (■) methamphetamine (METH) and sacrificed 2d later for determination of striatal levels of DAT by immunoblotting (a). Blots were quantified using ImageJ and data are mean ± SEM for 10–12 mice per group (b). *p < 0.01 or ***p < 0.0001 vs control (C) and #p < 0.01 or ##p < 0.001 vs the respective dose of methamphetamine (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Fig. 3a shows that mephedrone significantly increased methamphetamine-induced reductions in TH levels as determined by immunoblotting. Immunoblots were quantified and in agreement with results above for DA and DAT, the main effects of methamphetamine dose (F1,81 = 47.89, p < 0.0001) and mephedrone dose (F4,81 = 63.57, p < 0.0001) were highly significant by two-way ANOVA (Fig. 3b). The main effect of mephedrone given in combination with either 2.5 mg/kg (F4,34 = 12.98, p < 0.0001) or 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,49 = 99.16, p < 0.0001) was also highly significant by one-way ANOVA. All treatments with either dose of methamphetamine ± mephedrone caused significantly greater reductions in TH by comparison to the respective control (p < 0.001 for 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine + 10 mg/kg mephedrone; p < 0.0001 for all other combinations) with the exception of 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine alone which did not significantly change TH levels (i.e., no toxicity). Fig. 3b also shows that mephedrone doses of 20 mg/kg (p < 0.01) and 40 mg/kg (p < 0.001) significantly enhanced the reductions in TH caused by 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine and all three doses of mephedrone significantly (p < 0.0001) enhanced the effects of 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine on TH reductions.

Fig. 3

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced reductions in striatal TH. Mice were treated with the indicated doses of mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 2.5 (●) or 5.0 mg/kg (■) methamphetamine (METH) and sacrificed 2d later for determination of striatal levels of TH by immunoblotting (a). Blots were quantified using ImageJ and data are mean ± SEM for 10–12 mice per group (b). Some error bars were too small to exceed the size of the symbols and do not appear visible. **p < 0.001 or ***p < 0.0001 vs control (C) and #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.001 or ###p < 0.0001) vs the respective dose of methamphetamine (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced hyperthermia

Mephedrone, like methamphetamine, causes significant hyperthermia (Hadlock et al. 2011, Baumann et al. 2012, Angoa-Perez et al. 2012). When mephedrone was given 30 min before each injection of methamphetamine, it can be seen in Fig. 4 that the main effects of methamphetamine and mephedrone doses (F1,300 = 11.99, p < 0.0001) over time (F4,300 = 51.73, p < 0.0001) were highly significant by two-way ANOVA. The main effects of mephedrone given in combination with either 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,120 = 41.44, p < 0.0001, panel a) over time (F30,120 = 3.84, p < 0.0001) or 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,120 = 78.09, p < 0.0001, panel b) over time (F30,120 = 9.98, p < 0.0001) were also highly significant by two-way ANOVA. All treatments with either dose of methamphetamine ± mephedrone were significantly different from the respective controls (p < 0.0001 for all treatments).

Fig. 4

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced hyperthermia. Mice were treated with the indicated doses of mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 2.5 (a) or 5.0 mg/kg (b) methamphetamine (METH). Core temperatures were measured at 20 min intervals by telemetry starting 60 min before the first injection of methamphetamine. The 4 methamphetamine injections are indicated by the arrows resting on the x-axis. Data are expressed as mean body temperature of 6–8 mice per group. SEMs were always < 10% of the mean and are omitted for the sake of clarity.

Effects of mephedrone on amphetamine- and MDMA-induced neurotoxicity

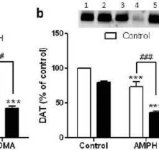

In order to test if the enhancing effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine could be extended to other neurotoxic amphetamines, mice were treated with this β-ketoamphetamine (20 mg/kg) plus amphetamine (4X 5 mg/kg) or MDMA (4X 20 mg/kg) and the results are presented in Fig. 5. Recall that mephedrone itself does not reduce striatal DA, DAT or TH (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012). The main effect of drug (F5,27 = 27.18, p < 0.0001) was highly significant by one-way ANOVA for DA reductions (Fig. 5a). It can also be seen in Fig. 5a that all treatments with amphetamine (p < 0.001) or MDMA (p < 0.001) alone or in combination with mephedrone (p < 0.0001 for both drugs) significantly lowered DA levels from control. Mephedrone significantly enhanced DA reductions caused by amphetamine (p < 0.01) or MDMA (p < 0.01). Fig. 5b shows similar effects of combination drug treatments on DAT levels in striatum. The main effect of drug (F4,49 = 42.63, p < 0.0001) was highly significant by one-way ANOVA for DAT. It can also be seen in Fig. 5b that all treatments with amphetamine or MDMA were significantly (p < 0.0001 for all) lower by comparison to control. Mephedrone also significantly enhanced DAT reductions caused by either amphetamine or MDMA (p < 0.0001 in both cases). Finally, Fig. 5c shows that the main effect of drug (F4,50 = 75.06, p < 0.0001) was highly significant by one-way ANOVA for reductions in TH. It can also be seen in Fig. 5c that all treatments with amphetamine or MDMA were significantly (p < 0.0001 for all) lower by comparison to control. Mephedrone also significantly enhanced TH reductions caused by either amphetamine or MDMA (p < 0.0001 in both cases)

Fig. 5

Effects of mephedrone on amphetamine- or MDMA-induced DA nerve ending neurotoxicity. Mice were treated with 20 mg/kg mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 5.0 mg/kg amphetamine (AMPH) or 20 mg/kg MDMA and sacrificed 2d after treatment for determination of striatal levels of (a) DA by HPLC. (b) DAT and (c) TH were determined by immunoblotting and blots were quantified using ImageJ. Representative immunoblots for DAT and TH are included as insets to panels (b) and (c) respectively and treatments for both panels are indicated by 1,5: control; 2,6: MEPH; 3: AMPH; 4: AMPH + MEPH; 7: MDMA; and 8: MDMA + MEPH. Data are mean ± SEM for 5–12 mice in each group. **p < 0.001 or ***p < 0.0001 vs control and #p < 0.01 or ###p < 0.0001 vs AMPH or MDMA (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Effects of nomifensine on methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity

Nomifensine, a powerful DAT blocker with no known abuse or neurotoxic potential, was tested for its ability to protect against methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity and for contrast to the actions of mephedrone on the toxicity to DA nerve endings caused by methamphetamine, amphetamine and MDMA. Results in Fig. 6a show that the main effect of drug (F3,16 = 63.39, p < 0.0001) on DA levels was highly significant by one-way ANOVA. Nomifensine alone did not alter DA levels but the reduction caused by methamphetamine (p < 0.0001) was slightly but significantly reversed by nomifensine (p < 0.01). The main effect of drug (F3,20 = 16.78, p < 0.0001) on DAT levels was highly significant by one-way ANOVA as shown in Fig. 6b. Nomifensine did not change DAT levels but provided significant protection (p < 0.001) against the reduction in striatal DAT caused by methamphetamine (p < 0.0001) in comparison to control. Finally, Fig. 6c shows that the main effect of drug (F3,15 = 14.10, p < 0.0001) on TH levels was highly significant by one-way ANOVA. As seen for DA and DAT, the reduction in TH caused by methamphetamine (p < 0.0001) was slightly but significantly prevented by nomifensine (p < 0.01).

Fig. 6

Effects of nomifensine on methamphetamine-induced DA nerve ending neurotoxicity. Mice were treated with 5.0 mg/kg nomifensine (NOM) 30 min prior to each injection of 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (METH) and sacrificed 2d later for determination of striatal levels of (a) DA by HPLC. (b) DAT and (c) TH were determined by immunoblotting and blots were quantified using ImageJ. Representative immunoblots for DAT and TH are included as insets to panels (b) and (c) respectfully. Data are mean plus SEM for 5–7 mice per group. ***p < 0.0001 vs control (C) and #p < 0.01 or ##p < 0.001 vs methamphetamine alone (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to determine if mephedrone would prevent DA nerve ending toxicity caused by methamphetamine. Based on its chemical similarity to methamphetamine and MDMA, it was initially expected that mephedrone would exert damaging effects on the DA neuronal system. However, several studies established almost simultaneously that mephedrone was not toxic to DA nerve endings (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012, Baumann et al. 2012, Hadlock et al. 2011). The question of whether this drug causes damage to the 5-HT neuronal system remains open. One study reported persistent reductions in 5-HT nerve ending function (Hadlock et al. 2011) while another found that mephedrone did not cause damage (Baumann et al. 2012). Mephedrone interacts with the DA nerve ending in a manner that suggests that it indeed stimulates release and blocks DA re-uptake via its interactions with the DAT. A key facet of the neurotoxic mechanism of action of methamphetamine is its ability to gain access to DA nerve endings through the DAT and disrupt DA homeostasis (Sulzer 2011). If this early step in the methamphetamine neurotoxic cascade is prevented by inhibition of the DAT, toxicity is prevented (Pu et al. 1994, Poth et al. 2012, Marek et al. 1990, Schmidt and Gibb 1985). We reasoned that mephedrone could have this same protective property as other DAT inhibitors but observed instead a significant enhancement of toxicity. This interaction was seen using two different doses of methamphetamine that cause moderate or severe damage to DA nerve endings (4X 2.5 or 5.0 mg/kg, respectively). This potentiating effect of mephedrone was not restricted to methamphetamine and extended to amphetamine and MDMA, two drugs that are often co-abused with mephedrone and other β-ketoamphetamines (Feyissa and Kelly 2008, Schifano et al. 2011, Kelly 2011). Therefore, despite the fact that mephedrone does not cause toxicity to at least DA nerve endings of the striatum, it potentiates the neurotoxic effects of other drugs of abuse. This new finding should cast mephedrone abuse in even more stark terms because its lack of intrinsic neurotoxicity may make it appear innocuous.

Hyperthermia is a commonly reported acute adverse effect of methamphetamine (Greene et al. 2008) and β-ketoamphetamine ingestion in humans (Borek and Holstege 2012, Prosser and Nelson 2012). Like methamphetamine, many of the β-ketoamphetamine drugs also cause significant elevations in core temperature in rodents (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012, Hadlock et al. 2011, Baumann et al. 2012, Rockhold et al. 1997). While the hyperthermia caused by methamphetamine could contribute to its morphological and neuronal damaging effects, it is not necessarily the case that hyperthermia is the direct cause of these effects (Kiyatkin and Sharma 2009). We recorded core body temperatures in mice treated with mephedrone and methamphetamine and observed that the combined treatment did not increase temperatures beyond the maximal increases seen after either drug alone. Methamphetamine caused a dose-related increase in body temperature and this hyperthermia was invariant over the entire mephedrone dose range tested. In fact, the post-injection fall in body temperature observed after mephedrone treatment (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012) was retained at higher doses of mephedrone plus methamphetamine. Even though the drug-induced hyperthermia was not enhanced by combined drug treatment, the neurotoxic effects were additive. Therefore, at least in the present case, it appears that the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine can be enhanced by mephedrone in a manner that is independent of hyperthermia.

Mephedrone clearly inhibits DAT function and blocks DA re-uptake in vitro (Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012, Hadlock et al. 2011, Kehr et al. 2011, Martinez-Clemente et al. 2012, Cozzi et al. 1999). Mephedrone displaces WIN-35,428 from its binding site on the DAT, suggesting that it is a competitive inhibitor of DA uptake (Martinez-Clemente et al. 2012, Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012). The potency of mephedrone in this regard is very similar to that of methamphetamine (Cozzi et al. 1999) and MDMA (Escubedo et al. 2011). It is not known if mephedrone is transported by the DAT but methcathinone is (Cozzi and Foley 2003). Nomifensine and amphonelic acid, which bind to the DAT and inhibit DA uptake, provide substantial protection against methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity (Pu et al. 1994, Marek et al. 1990, Schmidt and Gibb 1985, Poth et al. 2012) and mice lacking the DAT are resistant to the neuronal toxicity of methamphetamine (Fumagalli et al. 1998). Knowing that mephedrone is non-neurotoxic and a DAT blocker leads to the prediction that it should prevent toxicity. We tested nomifensine in this regard as a positive control and confirmed that it protects against methamphetamine-induced depletion of DA, DAT and TH. Nomifensine also inhibits the norepinephrine transporter (Brogden et al. 1979) but this property cannot explain the present results because most β-ketoamphetamines including mephedrone inhibit the norepinephrine transporter and block norepinephrine uptake (Kelly 2011, Rothman et al. 2003, Cozzi et al. 1999, Sogawa et al. 2011, Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012). A role for the 5-HT neuronal system in some of the pharmacological actions of mephedrone is possible in light of the ability of this drug, like MDMA (Yamamoto et al. 1995), to cause efflux of striatal DA via its interactions with 5-HT2A receptors (Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012, Martinez-Clemente et al. 2012). The hyper-locomotion caused by mephedrone is dependent on endogenous 5-HT (Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012) and this drug also stimulates the release of 5-HT and inhibits its uptake in vitro (Sogawa et al. 2011, Cozzi et al. 1999, Nagai et al. 2007, Hadlock et al. 2011, Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012, Martinez-Clemente et al. 2012) and in vivo (Baumann et al. 2012, Kehr et al. 2011). However, we can rule out a role for endogenous 5-HT in the DA neurotoxicity of at least methamphetamine by showing that mice genetically depleted of 5-HT retain their sensitivity to neurotoxicity (Thomas et al. 2010).

Mephedrone could enhance methamphetamine neurotoxicity by several possible mechanisms. First, mephedrone could interact with the VMAT to cause leakage of DA into the cytoplasm of the presynaptic nerve ending. Treatments that increase the cytoplasmic pool (i.e., drug-releasable) of DA increase methamphetamine neurotoxicity (Thomas et al. 2008, Thomas et al. 2009, Schmidt et al. 1985). This mechanism is not likely because methcathinone interacts only weakly with the VMAT (Cozzi et al. 1999). Second, the combination of mephedrone plus methamphetamine could have a synergistic effect on non-vesicular release of DA but this possibility also seems unlikely in light of results showing that treatment of DAT- or SERT-expressing CHO cells with methylone plus methamphetamine does not have an additive effect on DA or 5-HT release (Sogawa et al. 2011). Third, mephedrone could interact with the DAT in a novel manner that contributes to additive toxicity. It has been demonstrated that methylone in combination with methamphetamine causes synergistic cytotoxicity in CHO cells expressing the DAT or SERT but not in wild type CHO cells lacking the transporters (Sogawa et al. 2011). The cytotoxicity seen in cultured cells in these studies (i.e., LDH release) is very different from the damage to DA nerve endings caused by methamphetamine but this mechanism suggests an interesting but undefined role for the DAT in heightened cytotoxicity. Last, mephedrone could change methamphetamine metabolism. Mephedrone is primarily metabolized by N-demethylation (Meyer and Maurer 2010) as are methamphetamine and MDMA (Caldwell 1976). Support for this mechanism comes from the demonstration that methamphetamine and MDMA mutually inhibit the production of their respective primary metabolites and elevate drug plasma levels above those seen after administration of either drug alone (Kuwayama et al. 2012). The doses of mephedrone used presently and in our previous study (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012), while high, are non-neurotoxic and fall within the range abused by humans (McErath and O'Neill 2011). Therefore, mephedrone could be acting like MDMA to increase the plasma levels of methamphetamine by inhibiting its metabolism. An in-depth pharmacokinetic analysis will be required to confirm this latter possibility.

Abuse of the β-ketoamphetamines is increasing at an alarming rate and mephedrone is now one of the most commonly used drugs following cannabis, MDMA and cocaine (Morris 2010, Winstock et al. 2011b). In addition, mephedrone induces stronger feelings of craving in humans by comparison to MDMA (Brunt et al. 2011) and users who snort mephedrone rate it as more addictive than cocaine (Winstock et al. 2011b). Mephedrone is consumed by humans in a binge-like fashion (i.e., “stacking”) and is often taken with other drugs such as cannabis and the amphetamine psychostimulants (Schifano et al. 2011, Fass et al. 2012, Winstock et al. 2011a, Kelly 2011, Torrance and Cooper 2010). Mephedrone is found increasingly in tablets sold as MDMA (Brunt et al. 2011) and its use will likely surpass that of MDMA as the purity of this latter drug continues to fall (Brunt et al. 2011, Tanner-Smith 2006, Teng et al. 2006). Based on the common patterns of abuse of mephedrone and other “bath salts” ingredients, it is important to consider if additional health risks accrue in humans when these drugs are combined with the amphetamines purposely or unwittingly. Our results showing that at least mephedrone significantly enhances the neurotoxicity to DA nerve endings of the striatum caused by methamphetamine, amphetamine and MDMA reveal a particularly dangerous and unexpected property of this β-ketoamphetamine.

Abbreviations used

5-HT serotonin

DA dopamine

DAT DA transporter

MDMA 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine

TH tyrosine hydroxylase

VMAT vesicular monoamine transporter

Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone) is a cathinone derivative and structural analog of methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA). Mephedrone is one psychoactive ingredient of “bath salts” along with other compounds such as methylone, butylone and 3, 4- methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). β-ketoamphetamines are being abused at increasing rates due in no small part to the highly restricted availability of precursors needed for the synthesis of methamphetamine and MDMA in clandestine labs and a corresponding reduction in their purity (Winstock et al. 2011b, Brunt et al. 2011). As abuse of β-ketoamphetamines continues to rise, the list of their adverse effects has grown to include cardiovascular complications, agitation, insomnia, psychosis and depression (Schifano et al. 2011, Prosser and Nelson 2012).

As chemical congeners of methamphetamine and MDMA, it is not surprising that the β-ketoamphetamines have many of the same effects as these former drugs on the central nervous system. For example, these drugs block dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) transporters (DAT and SERT, respectively) (Cozzi et al. 1999, Rothman et al. 2003, Fleckenstein et al. 2000, Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012) and they stimulate monoamine release in vitro (Kalix and Glennon 1986, Gygi et al. 1997, Rothman et al. 2003) and in vivo (Gygi et al. 1997, Kehr et al. 2011). Methcathinone causes persistent reductions tryptophan hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) activity and depletion of DA and 5-HT (Gygi et al. 1997, Gygi et al. 1996, Sparago et al. 1996). PET imaging studies in abstinent methcathinone users revealed reduced striatal DAT density suggesting a loss of DA terminals (McCann et al. 1998). The simultaneous stimulation of DA release and inhibition of its uptake mirror the critical elements underlying the neurotoxicity associated with methamphetamine (Kuhn et al. 2008, Yamamoto and Bankson 2005, Cadet et al. 2007, Fleckenstein et al. 2007).

We (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012) and others (Baumann et al. 2012, Hadlock et al. 2011) recently investigated the possibility that mephedrone could cause neurotoxicity like methamphetamine and MDMA. Surprisingly, mephedrone was not toxic to DA nerve endings of the striatum (Hadlock et al. 2011, Baumann et al. 2012, Angoa-Perez et al. 2012). The issue of whether mephedrone damages 5-HT nerve endings remains unsettled as one study documented positive effects (Hadlock et al. 2011) while another was negative (Baumann et al. 2012). In light of the relatively benign effect of mephedrone on DA nerve endings and considering its properties as a DAT blocker, we hypothesized that it could actually protect the DA neuronal system from the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine much as is known to occur with other DAT blockers such as amphonelic acid (Pu et al. 1994, Schmidt and Gibb 1985, Marek et al. 1990) and nomifensine (Poth et al. 2012). We report presently that mephedrone significantly enhances the neurotoxicity of methamphetamine. This effect extends to amphetamine and MDMA, drugs that are often co-abused with mephedrone (Feyissa and Kelly 2008, Schifano et al. 2011). These surprising results cast the abuse of mephedrone in a new light and add urgency to recognition of this subtle and dangerous property of this β-ketoamphetamine.

Materials and methods

Drugs and Reagents

Mephedrone hydrochloride and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) were obtained from the NIDA Research Resources Drug Supply Program. (+) Methamphetamine hydrochloride, nomifensine maleate, d-amphetamine sulfate, pentobarbital, DA, and all buffers and HPLC reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Bicinchoninic acid protein assay kits were obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Polyclonal antibodies against rat TH were produced as previously described (Kuhn and Billingsley 1987). Monoclonal antibodies against rat DAT were generously provided by Dr. Roxanne A. Vaughan (University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND, USA). HRP-conjugated anti-IgG secondary antibodies were provided by Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA, USA).

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) weighing 20–25 g at the time of experimentation were housed 5 per cage in large shoe-box cages in a light (12 h light/dark) and temperature controlled room. Female mice were used because they are known to be very sensitive to neuronal damage by the neurotoxic amphetamines and to maintain consistency with our previous studies of methamphetamine neurotoxicity (Thomas et al. 2010, Thomas et al. 2008, Thomas et al. 2009). Mice had free access to food and water. The Institutional Care and Use Committee of Wayne State University approved the animal care and experimental procedures. All procedures were also in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Pharmacological, physiological and behavioral procedures

Mice were treated with mephedrone using a binge-like regimen comprised of 4 injections of 10, 20 or 40 mg/kg with a 2 h interval between each injection. This binge treatment regimen, when used to inject substituted amphetamines and cathinone derivatives, results in extensive DA nerve ending damage. The doses of mephedrone used presently were previously shown to be non-toxic to DA nerve endings (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012). Mice were treated with methamphetamine (4X 2.5 or 5 mg/kg), amphetamine (4X 5 mg/kg) or MDMA (4X 20 mg/kg) alone or in combination with mephedrone. When treated with two drugs, mice received a mephedrone injection 30 min prior to each of the 4 injections of methamphetamine, amphetamine or MDMA. Controls received injections of physiological saline on the same schedule used for mephedrone alone or in combination with other amphetamines. As a control for the effects of a DAT inhibitor on methamphetamine toxicity, mice were treated with nomifensine (4X 5 mg/kg) 30 min prior to each injection of methamphetamine (4X 5 mg/kg). All injections were given via the i.p. route. Mice were sacrificed 2 days after the last drug treatment when amphetamine-associated neurotoxicity has reached maximum. Body temperature was monitored by telemetry using IPTT-300 implantable temperature transponders from Bio Medic Data Systems, Inc. (Seaford, DE, USA). Temperatures were recorded non-invasively every 20 min starting 60 min before the first METH injection and continuing for 9 h thereafter using the DAS-5001 console system from Bio Medic.

Determination of striatal DA content

Striatal tissue was dissected bilaterally from the brain after treatment and stored at −80°C. Frozen tissues were weighed and sonicated in 10 volumes of 0.16 N perchloric acid at 4°C. Insoluble protein was removed by centrifugation and DA was determined by HPLC with electrochemical detection as previously described for methamphetamine (Thomas et al. 2010, Thomas et al, 2009).

Determination of TH and DAT protein levels by immunoblotting

The effects of drug treatments on striatal TH and DAT levels were determined by immunoblotting as an index of toxicity to striatal DA nerve endings. Mice were sacrificed by decapitation after treatment and striatum was dissected bilaterally. Tissue was stored at −80°C. Frozen tissue was disrupted by sonication in 1% SDS at 95°C and insoluble material was sedimented by centrifugation. Protein was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method and equal amounts of protein (70 μg/lane) were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then electroblotted to nitrocellulose. Blots were blocked in Tris buffered saline containing Tween 20 (0.1% v/v) and 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies against TH (1:1000) or DAT (1:1000) were added to blots and allowed to incubate for 16 h at 4°C. Blots were washed 3X in Tris-buffered saline to remove unreacted antibodies and then incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-IgG secondary antibody (1:4000) for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence and the relative densities of TH- and DAT-reactive bands were determined by imaging with a Kodak Image Station (Carestream Molecular Systems, Rochester, NY, USA) and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH).

Data analysis

Two-way ANOVAs were performed to analyze the dose effects of methamphetamine versus mephedrone on DA, DAT and TH. The effects of drug treatments on striatal DA, TH and DAT content were tested for significance by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. Results of drug treatments on core body temperature over time were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test to determine significance of differences in temperature at individual times after treatment. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 5.02 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com).

Go to:

Results

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity

Mephedrone, in doses (10, 20 or 40 mg/kg) known not to cause DA nerve ending toxicity (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012) was administered 30 min before each injection of methamphetamine. Methamphetamine was administered in doses that cause moderate (4X 2.5 mg/kg) or severe (4X 5 mg/kg) damage to DA nerve endings of the striatum (Thomas et al. 2004, Thomas et al. 2010). Results presented in Fig. 1 show that the main effects of methamphetamine dose (F1,40 = 66.60, p < 0.0001) and mephedrone dose (F4,40 = 131.3, p < 0.0001) on DA levels in striatum were highly significant by two-way ANOVA. The main effect of mephedrone given in combination with either 2.5 mg/kg (F4,22 = 35.96, p < 0.001) or 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,17 = 953.9, p < 0.0001) was also highly significant by one-way ANOVA. All treatments with either dose of methamphetamine ± mephedrone caused significantly greater reductions in DA by comparison to the respective control (p < 0.0001 for all). Fig. 1 also shows that mephedrone doses of 20 (p < 0.01) and 40 mg/kg (p < 0.001) significantly enhanced the depleting effects of 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine on DA whereas all doses of mephedrone significantly enhanced the effects of 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine on DA levels (p < 0.0001 for all).

Fig.1

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced reductions in striatal DA. Mice were treated with the indicated doses of mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 2.5 (•) or 5.0 mg/kg (■) methamphetamine (METH) and sacrificed 2d later for determination of striatal levels of DA by HPLC. Data are mean ± SEM for 5–7 mice per group. Some error bars were too small to exceed the size of the symbols and do not appear visible. ***p < 0.001 vs controls and #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.001 or ###p < 0.0001 vs the respective dose of methamphetamine (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Fig. 2a shows that mephedrone significantly increased methamphetamine-induced reductions in DAT levels as determined by immunoblotting. Immunoblots were quantified and in agreement with results for DA, the main effects of methamphetamine dose (F1,92 = 9.48, p < 0.001) and mephedrone dose (F4,92 = 37.56, p < 0.0001) on DAT levels in striatum were highly significant by two-way ANOVA (Fig. 2b). The main effect of mephedrone given in combination with either 2.5 mg/kg (F4,56 = 15.55, p < 0.0001) or 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,39 = 24.84, p < 0.0001) was also highly significant by one-way ANOVA. All treatments with either dose of methamphetamine ± mephedrone caused significantly greater reductions in DAT by comparison to the respective control (p < 0.01 for 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine alone; p < 0.0001 for all other treatments). Fig. 2b also shows that mephedrone doses of 20 mg/kg (p < 0.01) and 40 mg/kg (p < 0.001) significantly enhanced the reductions in DAT caused by 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine whereas only the 40 mg/kg mephedrone dose significantly enhanced (p < 0.01) the effects of 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine on DAT reductions.

Fig.2

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced reductions in striatal DAT. Mice were treated with the indicated doses of mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 2.5 (●) or 5.0 mg/kg (■) methamphetamine (METH) and sacrificed 2d later for determination of striatal levels of DAT by immunoblotting (a). Blots were quantified using ImageJ and data are mean ± SEM for 10–12 mice per group (b). *p < 0.01 or ***p < 0.0001 vs control (C) and #p < 0.01 or ##p < 0.001 vs the respective dose of methamphetamine (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Fig. 3a shows that mephedrone significantly increased methamphetamine-induced reductions in TH levels as determined by immunoblotting. Immunoblots were quantified and in agreement with results above for DA and DAT, the main effects of methamphetamine dose (F1,81 = 47.89, p < 0.0001) and mephedrone dose (F4,81 = 63.57, p < 0.0001) were highly significant by two-way ANOVA (Fig. 3b). The main effect of mephedrone given in combination with either 2.5 mg/kg (F4,34 = 12.98, p < 0.0001) or 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,49 = 99.16, p < 0.0001) was also highly significant by one-way ANOVA. All treatments with either dose of methamphetamine ± mephedrone caused significantly greater reductions in TH by comparison to the respective control (p < 0.001 for 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine + 10 mg/kg mephedrone; p < 0.0001 for all other combinations) with the exception of 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine alone which did not significantly change TH levels (i.e., no toxicity). Fig. 3b also shows that mephedrone doses of 20 mg/kg (p < 0.01) and 40 mg/kg (p < 0.001) significantly enhanced the reductions in TH caused by 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine and all three doses of mephedrone significantly (p < 0.0001) enhanced the effects of 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine on TH reductions.

Fig. 3

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced reductions in striatal TH. Mice were treated with the indicated doses of mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 2.5 (●) or 5.0 mg/kg (■) methamphetamine (METH) and sacrificed 2d later for determination of striatal levels of TH by immunoblotting (a). Blots were quantified using ImageJ and data are mean ± SEM for 10–12 mice per group (b). Some error bars were too small to exceed the size of the symbols and do not appear visible. **p < 0.001 or ***p < 0.0001 vs control (C) and #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.001 or ###p < 0.0001) vs the respective dose of methamphetamine (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced hyperthermia

Mephedrone, like methamphetamine, causes significant hyperthermia (Hadlock et al. 2011, Baumann et al. 2012, Angoa-Perez et al. 2012). When mephedrone was given 30 min before each injection of methamphetamine, it can be seen in Fig. 4 that the main effects of methamphetamine and mephedrone doses (F1,300 = 11.99, p < 0.0001) over time (F4,300 = 51.73, p < 0.0001) were highly significant by two-way ANOVA. The main effects of mephedrone given in combination with either 2.5 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,120 = 41.44, p < 0.0001, panel a) over time (F30,120 = 3.84, p < 0.0001) or 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (F4,120 = 78.09, p < 0.0001, panel b) over time (F30,120 = 9.98, p < 0.0001) were also highly significant by two-way ANOVA. All treatments with either dose of methamphetamine ± mephedrone were significantly different from the respective controls (p < 0.0001 for all treatments).

Fig. 4

Effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine-induced hyperthermia. Mice were treated with the indicated doses of mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 2.5 (a) or 5.0 mg/kg (b) methamphetamine (METH). Core temperatures were measured at 20 min intervals by telemetry starting 60 min before the first injection of methamphetamine. The 4 methamphetamine injections are indicated by the arrows resting on the x-axis. Data are expressed as mean body temperature of 6–8 mice per group. SEMs were always < 10% of the mean and are omitted for the sake of clarity.

Effects of mephedrone on amphetamine- and MDMA-induced neurotoxicity

In order to test if the enhancing effects of mephedrone on methamphetamine could be extended to other neurotoxic amphetamines, mice were treated with this β-ketoamphetamine (20 mg/kg) plus amphetamine (4X 5 mg/kg) or MDMA (4X 20 mg/kg) and the results are presented in Fig. 5. Recall that mephedrone itself does not reduce striatal DA, DAT or TH (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012). The main effect of drug (F5,27 = 27.18, p < 0.0001) was highly significant by one-way ANOVA for DA reductions (Fig. 5a). It can also be seen in Fig. 5a that all treatments with amphetamine (p < 0.001) or MDMA (p < 0.001) alone or in combination with mephedrone (p < 0.0001 for both drugs) significantly lowered DA levels from control. Mephedrone significantly enhanced DA reductions caused by amphetamine (p < 0.01) or MDMA (p < 0.01). Fig. 5b shows similar effects of combination drug treatments on DAT levels in striatum. The main effect of drug (F4,49 = 42.63, p < 0.0001) was highly significant by one-way ANOVA for DAT. It can also be seen in Fig. 5b that all treatments with amphetamine or MDMA were significantly (p < 0.0001 for all) lower by comparison to control. Mephedrone also significantly enhanced DAT reductions caused by either amphetamine or MDMA (p < 0.0001 in both cases). Finally, Fig. 5c shows that the main effect of drug (F4,50 = 75.06, p < 0.0001) was highly significant by one-way ANOVA for reductions in TH. It can also be seen in Fig. 5c that all treatments with amphetamine or MDMA were significantly (p < 0.0001 for all) lower by comparison to control. Mephedrone also significantly enhanced TH reductions caused by either amphetamine or MDMA (p < 0.0001 in both cases)

Fig. 5

Effects of mephedrone on amphetamine- or MDMA-induced DA nerve ending neurotoxicity. Mice were treated with 20 mg/kg mephedrone (MEPH) 30 min prior to each injection of 5.0 mg/kg amphetamine (AMPH) or 20 mg/kg MDMA and sacrificed 2d after treatment for determination of striatal levels of (a) DA by HPLC. (b) DAT and (c) TH were determined by immunoblotting and blots were quantified using ImageJ. Representative immunoblots for DAT and TH are included as insets to panels (b) and (c) respectively and treatments for both panels are indicated by 1,5: control; 2,6: MEPH; 3: AMPH; 4: AMPH + MEPH; 7: MDMA; and 8: MDMA + MEPH. Data are mean ± SEM for 5–12 mice in each group. **p < 0.001 or ***p < 0.0001 vs control and #p < 0.01 or ###p < 0.0001 vs AMPH or MDMA (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Effects of nomifensine on methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity

Nomifensine, a powerful DAT blocker with no known abuse or neurotoxic potential, was tested for its ability to protect against methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity and for contrast to the actions of mephedrone on the toxicity to DA nerve endings caused by methamphetamine, amphetamine and MDMA. Results in Fig. 6a show that the main effect of drug (F3,16 = 63.39, p < 0.0001) on DA levels was highly significant by one-way ANOVA. Nomifensine alone did not alter DA levels but the reduction caused by methamphetamine (p < 0.0001) was slightly but significantly reversed by nomifensine (p < 0.01). The main effect of drug (F3,20 = 16.78, p < 0.0001) on DAT levels was highly significant by one-way ANOVA as shown in Fig. 6b. Nomifensine did not change DAT levels but provided significant protection (p < 0.001) against the reduction in striatal DAT caused by methamphetamine (p < 0.0001) in comparison to control. Finally, Fig. 6c shows that the main effect of drug (F3,15 = 14.10, p < 0.0001) on TH levels was highly significant by one-way ANOVA. As seen for DA and DAT, the reduction in TH caused by methamphetamine (p < 0.0001) was slightly but significantly prevented by nomifensine (p < 0.01).

Fig. 6

Effects of nomifensine on methamphetamine-induced DA nerve ending neurotoxicity. Mice were treated with 5.0 mg/kg nomifensine (NOM) 30 min prior to each injection of 5.0 mg/kg methamphetamine (METH) and sacrificed 2d later for determination of striatal levels of (a) DA by HPLC. (b) DAT and (c) TH were determined by immunoblotting and blots were quantified using ImageJ. Representative immunoblots for DAT and TH are included as insets to panels (b) and (c) respectfully. Data are mean plus SEM for 5–7 mice per group. ***p < 0.0001 vs control (C) and #p < 0.01 or ##p < 0.001 vs methamphetamine alone (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to determine if mephedrone would prevent DA nerve ending toxicity caused by methamphetamine. Based on its chemical similarity to methamphetamine and MDMA, it was initially expected that mephedrone would exert damaging effects on the DA neuronal system. However, several studies established almost simultaneously that mephedrone was not toxic to DA nerve endings (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012, Baumann et al. 2012, Hadlock et al. 2011). The question of whether this drug causes damage to the 5-HT neuronal system remains open. One study reported persistent reductions in 5-HT nerve ending function (Hadlock et al. 2011) while another found that mephedrone did not cause damage (Baumann et al. 2012). Mephedrone interacts with the DA nerve ending in a manner that suggests that it indeed stimulates release and blocks DA re-uptake via its interactions with the DAT. A key facet of the neurotoxic mechanism of action of methamphetamine is its ability to gain access to DA nerve endings through the DAT and disrupt DA homeostasis (Sulzer 2011). If this early step in the methamphetamine neurotoxic cascade is prevented by inhibition of the DAT, toxicity is prevented (Pu et al. 1994, Poth et al. 2012, Marek et al. 1990, Schmidt and Gibb 1985). We reasoned that mephedrone could have this same protective property as other DAT inhibitors but observed instead a significant enhancement of toxicity. This interaction was seen using two different doses of methamphetamine that cause moderate or severe damage to DA nerve endings (4X 2.5 or 5.0 mg/kg, respectively). This potentiating effect of mephedrone was not restricted to methamphetamine and extended to amphetamine and MDMA, two drugs that are often co-abused with mephedrone and other β-ketoamphetamines (Feyissa and Kelly 2008, Schifano et al. 2011, Kelly 2011). Therefore, despite the fact that mephedrone does not cause toxicity to at least DA nerve endings of the striatum, it potentiates the neurotoxic effects of other drugs of abuse. This new finding should cast mephedrone abuse in even more stark terms because its lack of intrinsic neurotoxicity may make it appear innocuous.

Hyperthermia is a commonly reported acute adverse effect of methamphetamine (Greene et al. 2008) and β-ketoamphetamine ingestion in humans (Borek and Holstege 2012, Prosser and Nelson 2012). Like methamphetamine, many of the β-ketoamphetamine drugs also cause significant elevations in core temperature in rodents (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012, Hadlock et al. 2011, Baumann et al. 2012, Rockhold et al. 1997). While the hyperthermia caused by methamphetamine could contribute to its morphological and neuronal damaging effects, it is not necessarily the case that hyperthermia is the direct cause of these effects (Kiyatkin and Sharma 2009). We recorded core body temperatures in mice treated with mephedrone and methamphetamine and observed that the combined treatment did not increase temperatures beyond the maximal increases seen after either drug alone. Methamphetamine caused a dose-related increase in body temperature and this hyperthermia was invariant over the entire mephedrone dose range tested. In fact, the post-injection fall in body temperature observed after mephedrone treatment (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012) was retained at higher doses of mephedrone plus methamphetamine. Even though the drug-induced hyperthermia was not enhanced by combined drug treatment, the neurotoxic effects were additive. Therefore, at least in the present case, it appears that the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine can be enhanced by mephedrone in a manner that is independent of hyperthermia.

Mephedrone clearly inhibits DAT function and blocks DA re-uptake in vitro (Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012, Hadlock et al. 2011, Kehr et al. 2011, Martinez-Clemente et al. 2012, Cozzi et al. 1999). Mephedrone displaces WIN-35,428 from its binding site on the DAT, suggesting that it is a competitive inhibitor of DA uptake (Martinez-Clemente et al. 2012, Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012). The potency of mephedrone in this regard is very similar to that of methamphetamine (Cozzi et al. 1999) and MDMA (Escubedo et al. 2011). It is not known if mephedrone is transported by the DAT but methcathinone is (Cozzi and Foley 2003). Nomifensine and amphonelic acid, which bind to the DAT and inhibit DA uptake, provide substantial protection against methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity (Pu et al. 1994, Marek et al. 1990, Schmidt and Gibb 1985, Poth et al. 2012) and mice lacking the DAT are resistant to the neuronal toxicity of methamphetamine (Fumagalli et al. 1998). Knowing that mephedrone is non-neurotoxic and a DAT blocker leads to the prediction that it should prevent toxicity. We tested nomifensine in this regard as a positive control and confirmed that it protects against methamphetamine-induced depletion of DA, DAT and TH. Nomifensine also inhibits the norepinephrine transporter (Brogden et al. 1979) but this property cannot explain the present results because most β-ketoamphetamines including mephedrone inhibit the norepinephrine transporter and block norepinephrine uptake (Kelly 2011, Rothman et al. 2003, Cozzi et al. 1999, Sogawa et al. 2011, Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012). A role for the 5-HT neuronal system in some of the pharmacological actions of mephedrone is possible in light of the ability of this drug, like MDMA (Yamamoto et al. 1995), to cause efflux of striatal DA via its interactions with 5-HT2A receptors (Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012, Martinez-Clemente et al. 2012). The hyper-locomotion caused by mephedrone is dependent on endogenous 5-HT (Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012) and this drug also stimulates the release of 5-HT and inhibits its uptake in vitro (Sogawa et al. 2011, Cozzi et al. 1999, Nagai et al. 2007, Hadlock et al. 2011, Lopez-Arnau et al. 2012, Martinez-Clemente et al. 2012) and in vivo (Baumann et al. 2012, Kehr et al. 2011). However, we can rule out a role for endogenous 5-HT in the DA neurotoxicity of at least methamphetamine by showing that mice genetically depleted of 5-HT retain their sensitivity to neurotoxicity (Thomas et al. 2010).

Mephedrone could enhance methamphetamine neurotoxicity by several possible mechanisms. First, mephedrone could interact with the VMAT to cause leakage of DA into the cytoplasm of the presynaptic nerve ending. Treatments that increase the cytoplasmic pool (i.e., drug-releasable) of DA increase methamphetamine neurotoxicity (Thomas et al. 2008, Thomas et al. 2009, Schmidt et al. 1985). This mechanism is not likely because methcathinone interacts only weakly with the VMAT (Cozzi et al. 1999). Second, the combination of mephedrone plus methamphetamine could have a synergistic effect on non-vesicular release of DA but this possibility also seems unlikely in light of results showing that treatment of DAT- or SERT-expressing CHO cells with methylone plus methamphetamine does not have an additive effect on DA or 5-HT release (Sogawa et al. 2011). Third, mephedrone could interact with the DAT in a novel manner that contributes to additive toxicity. It has been demonstrated that methylone in combination with methamphetamine causes synergistic cytotoxicity in CHO cells expressing the DAT or SERT but not in wild type CHO cells lacking the transporters (Sogawa et al. 2011). The cytotoxicity seen in cultured cells in these studies (i.e., LDH release) is very different from the damage to DA nerve endings caused by methamphetamine but this mechanism suggests an interesting but undefined role for the DAT in heightened cytotoxicity. Last, mephedrone could change methamphetamine metabolism. Mephedrone is primarily metabolized by N-demethylation (Meyer and Maurer 2010) as are methamphetamine and MDMA (Caldwell 1976). Support for this mechanism comes from the demonstration that methamphetamine and MDMA mutually inhibit the production of their respective primary metabolites and elevate drug plasma levels above those seen after administration of either drug alone (Kuwayama et al. 2012). The doses of mephedrone used presently and in our previous study (Angoa-Perez et al. 2012), while high, are non-neurotoxic and fall within the range abused by humans (McErath and O'Neill 2011). Therefore, mephedrone could be acting like MDMA to increase the plasma levels of methamphetamine by inhibiting its metabolism. An in-depth pharmacokinetic analysis will be required to confirm this latter possibility.

Abuse of the β-ketoamphetamines is increasing at an alarming rate and mephedrone is now one of the most commonly used drugs following cannabis, MDMA and cocaine (Morris 2010, Winstock et al. 2011b). In addition, mephedrone induces stronger feelings of craving in humans by comparison to MDMA (Brunt et al. 2011) and users who snort mephedrone rate it as more addictive than cocaine (Winstock et al. 2011b). Mephedrone is consumed by humans in a binge-like fashion (i.e., “stacking”) and is often taken with other drugs such as cannabis and the amphetamine psychostimulants (Schifano et al. 2011, Fass et al. 2012, Winstock et al. 2011a, Kelly 2011, Torrance and Cooper 2010). Mephedrone is found increasingly in tablets sold as MDMA (Brunt et al. 2011) and its use will likely surpass that of MDMA as the purity of this latter drug continues to fall (Brunt et al. 2011, Tanner-Smith 2006, Teng et al. 2006). Based on the common patterns of abuse of mephedrone and other “bath salts” ingredients, it is important to consider if additional health risks accrue in humans when these drugs are combined with the amphetamines purposely or unwittingly. Our results showing that at least mephedrone significantly enhances the neurotoxicity to DA nerve endings of the striatum caused by methamphetamine, amphetamine and MDMA reveal a particularly dangerous and unexpected property of this β-ketoamphetamine.

Abbreviations used

5-HT serotonin

DA dopamine

DAT DA transporter

MDMA 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine

TH tyrosine hydroxylase

VMAT vesicular monoamine transporter